For anyone of a literary or adventurous persuasion, the enduring appeal of Ernest Miller Hemingway requires little explanation. While some of his antics and opinions haven’t aged well, the pared-down purity of his writing remains unparalleled. Meanwhile, stories about his lifestyle—as a globe-hopping adventurer, a no-nonsense hard drinker and an unrepentant philanderer—are almost as interesting as the Nobel and Pulitzer prize-winning fiction it inspired. Unsurprisingly many fans, myself included, feel the lure of visiting the places featured in his most famous works. Pamplona, Spain, for the bloody bull run. Paris for its Left Bank cafés, Key West in Florida for fishing, or Havana for frozen daiquiris. But Vorarlberg, in Austria? Well, that’s not so frequently on the list.

The area’s relative obscurity in the Hemingway timeline has little to do with a lack of beauty. The Austrian Alps in winter have at least as much to offer as Idaho in autumn, or Venice in springtime. It’s not about the geography, either. Caught beneath the cresting waves of Tirol, Switzerland’s Graubunden, and Lichtenstein the area might have been inaccessible once, but it’s now easily reachable from Innsbruck or Zurich airports by train. In truth, it’s chiefly that while Hemingway never forgot about his time in the Montafon valley, Montafon has largely forgotten about Hemingway.

I only came across the connection by chance, while scrolling the internet late one night. While several of his works mention skiing—including his ski-themed 1924 short story Cross Country Snow—I had no idea he had decamped to Montafon for two back-to-back seasons exactly one hundred years ago, from 1924-1926. A spark was lit. I resolved to follow in his footsteps—or rather, his ski tracks—and explore what there was to see of his legacy myself.

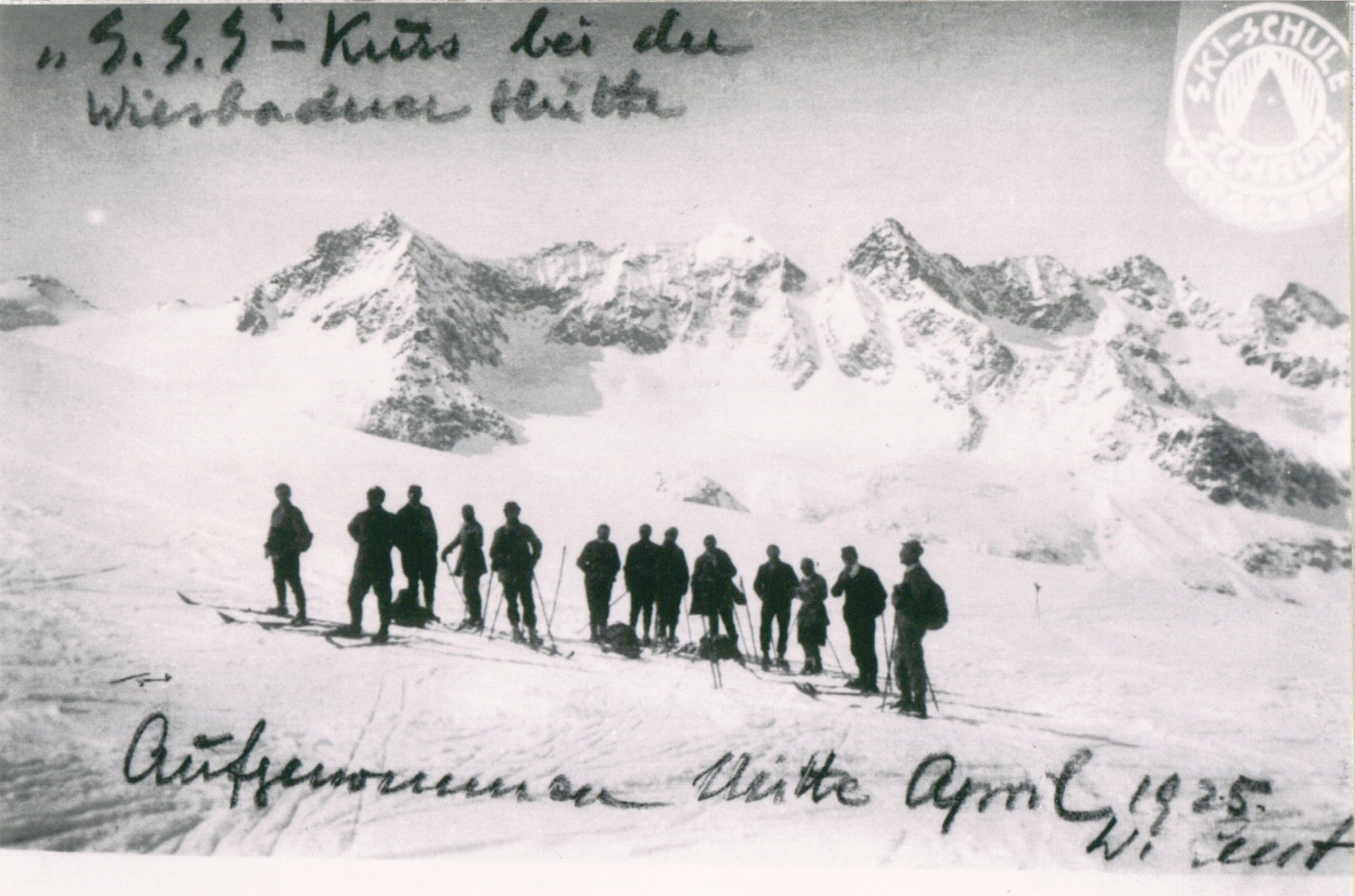

When he arrived in Austria, Hemingway was still waiting to break through as an author. He came because it was inexpensive. At the time, he was living largely off his wife’s private income, but working on The Sun Also Rises, his first novel. While in Austria, he learned that In Our Time, the collection of short stories which includes Cross Country Snow, had been accepted for publication in New York. In his letters, he talks of life on and off the mountains, gambling and drinking kirsch with locals in inns that reverberated with joyful mountain songs. He improved his skiing, became a member of the local ski club, and spent weeks ski touring high in the Silvretta Alps at the end of the Montafon Valley. He visited a number of refuges, among them the Madlenerhaus and the Wiesbadener Hütte. “We’d just done a hell of a glacier trip – a climb on skis to 3,200 metres… Jesus it was cold,” he wrote in one letter. “Then ran 5 miles down the face of the glacier in under 12 minutes. Wonderful country. The Silvretta.”

Today, the Montafon that Hemingway described remains very much intact. His description of Schruns as a sunny market town with stores, inns and a good, year-round hotel called the Taube, still resonates. The avalanche risks, of which Hemingway was well aware, still persist, as does the magical combination of snow and mountains. But the sense when I visited in mid-January was that his influence in the Vorarlberg was largely hidden. Unless, that is, one knew where to look.

Hills Like White Elephants

I began by checking into Gaschurn’s Hotel Rössle, with its inexpensive rooms, good beer, and schnapps. This is where Hemingway, his wife Hadley and infant son Bumby stayed throughout March 1926. Above to the west was Schwarzköpfle, wreathed in late afternoon mist. Below that, the densely-forested slopes of Versettla promising groomed runs and open-armed mountain restaurants. Skiers were rushing in from the cold after a long day on the slopes. The impression was of a pretty normal ski town, and it took until I met with sixth-generation owner, Gaby Keßler, to get a hint of the hotel’s literary history.

Even then, it involved being taken into a store cupboard squirrelled away at the back of the building, where, among pieces of broken furniture, I was shown a collection of vintage photographs, and a well-thumbed guestbook. Scanning her finger over one particular page, Keßler traced a line to the details of Hemingway’s stay, in the era when her grandparents ran the place. Far from being a prized endorsement, out on display, it felt like a whispered secret. “Guests aren’t so interested in this story today,” she explained, “but we hold onto these memories, as it helps tell the history of our hotel. Only after learning about his stay in the late 1990s, did I even read any Hemingway. I can see the Silvretta in his writing when he describes Kilimanjaro.”

“Scanning her finger over the page, she found his entry in the guest book”

The following morning I saw exactly what she meant. The forecast was good, the resort was buzzing with visiting skiers, and the slopes looked exactly as Hemingway described the summit of Africa’s highest mountain in The Snows of Kilimanjaro: “wide as all the world, great, high, and unbelievably white in the sun.” I set out in the company of Herby Berger, 70, a veteran guide who trained with Franz Klammer in the Austrian ski team, and has been guiding here for 50 years. He, too, read The Snows of Kilimanjaro when he was young, he told me. But it wasn’t until much later in life that he learnt it was written in the village he grew up in. “Hemingway should be a great anchor for the valley,” he told me, while we rode the Versettla cable car. “He was one of the original ski tour pioneers—not that anyone remembers really.”

Perhaps because of this collective amnesia, following the great writer’s exact tracks proved tricky. Of course, when Hemingway spent his winters here, these mountains were far more wild. Back then, it was ski touring or nothing—the first chairlift was only built here in 1947. Since then, however, Silvretta-Montafon, as the place is now known, has evolved into one of the largest resorts in Austria, with modern, high-speed lifts everywhere. It was a quick ascent up to the cols below Versettlaspitze, where we arrived to find rolling, perfectly groomed pistes. We knew Hemingway had ski toured there in leather shoes, clip bindings, and wooden skis, reaching the Madlenerhaus refuge, a mountain hut at 2,000m, which still does lively trade. Although it’s impossible to tell which exact route he followed on the descent, I felt like I was channelling some of his spirit as I snaked down towards the Nova, then Rinderhütte chairlifts.

From there, we tackled two of Montafon’s five ‘Black Scorpions’. Named for the venomous arachnids, these are incredibly steep runs of up to 67 percent gradient. We hurled down each one at a pace the old thrill-seeker would have approved of, and then, on the Bella Nova saddle, gazed out towards Gauertal, where Hemingway had once joined locals on expeditions for hunting trophies, skiing touring to the Lindauer Hütte. Unlike the rest of Montafon, Gauertal has resisted the lure of resort development—it felt a little like looking back in time, taking in a mountainscape that the writer would have recognised.

Nobody Ever Dies

Hemingway was no beginner when he arrived in Vorarlberg. In the previous years, he’d spent time in Chamby, Switzerland, and Cortina d’Ampezzo in the Dolomites, and so he hired guide and ski instructor Walther Lent to take him beyond the regular routes. “[Walther] believed the fun of skiing was to get up into the highest mountain country where there was no one else and where the snow was untracked and then travel from one high Alpine Club hut to another over the top passes and glaciers of the Alps,” Hemingway wrote in A Moveable Feast, his posthumously-published memoir.

Looking out across the Silvretta, now with a full day’s skiing in our legs, it was no surprise Hemingway fell for what the valley offered. It had all the elements that would go on to define his later life, and his work: adventure, risk, sensation, wilderness. It felt like a retreat from everything and only tangentially connected to the real world. “The American was right about one thing,” said Berger, my guide, as we discussed Montafon’s appeal. “This place is the best. I’ve been here all my life and I’ll never ski anywhere else.”

“The afternoon was for drinking—another of Hemingway’s great passions”

On my last day, I planned to stop in the village of Tschagguns, another spot where Hemingway had stayed a century ago. I spent the morning skiing in heavy snowfall with thick, smoky clouds, but as the flakes became fatter and the bitter cold started to bite, I decided the afternoon might be better-suited to contemplative drinking—another of Hemingway’s great passions—rather than skiing.

I stopped at Gasthof Löwen, a hotel dating from the 1500s where the writer used to smoke and sip schnapps after his long ski tours. “I’m surprised the old guy is still popular,” said Andreas Brugger, a teacher and local Hemingway expert who I’d arranged to meet at the bar. “His way of living—hunting, drinking, gambling, all the women—it is all very old fashioned. But the spell Hemingway casts is incredible. Maybe, it’s because he became such a traveller and us Austrians can proudly say he came here and loved it. It would be nice to think this story will continue. Maybe, at least, for another 100 years.”

Sitting with a kirsch, looking out at the blustery snow outside, I was struck by how similar things must have looked a century ago. The decor, for the most part, was the same. The mounted deer heads and hanging cowbells. So too, were these tables and chairs. This is as close to the Hemingway myth that most skiers can get, I thought. I could easily imagine him as a young man, still sitting in the near-empty bar, gathering his thoughts after an inspiring day on the mountain, and preparing for his destiny: a lifetime of adventures, as one of history’s most celebrated storytellers.

Perhaps, though, he’d have joined me for a drink first.

Snowhow

Our trip

Mike MacEacheran’s visit was supported by Vorarlberg Tourism. Their website is full of tips on where to go and what to do.

Where to stay

Mike stayed at the 200-year-old Posthotel Rössle, a cosy, four star property in the village of Gaschurns, which has been run by the Keßler family for five generations.

What to read

Hemingway’s short story collection In Our Time contains his best fictional description of skiing, in the story Cross Country Snow. But it’s his posthumous autobiography, A Moveable Feast, and his letters from the period, published as volume 2 of The Letters of Ernest Hemingway: 1923-25, that really shed light on his time in Montafon.